Revolutionizing Cardiac Surgery with a Heart: Dr. Tirone David on Surgery, Science, and Lifelong Learning

- Home

- Revolutionizing Cardiac Surgery with a Heart: Dr. Tirone David on Surgery, Science, and Lifelong Learning

Revolutionizing Cardiac Surgery with a Heart: Dr. Tirone David on Surgery, Science, and Lifelong Learning

Some people follow the rules. Others rewrite them. Meet Dr. Tirone David, the cardiac surgeon who transformed heart surgery and redefined the pursuit of medical perfection. With over 15,000 open-heart surgeries and 16 pioneering techniques, he’s not just saving lives—he’s reshaping the future of cardiovascular medicine. Guided by curiosity, mentorship, and an insatiable drive to innovate, his journey is one of relentless improvement. This isn’t just an interview—it’s a rare glimpse into the mind of a master surgeon, a lesson in discipline, and an invitation to rethink everything we thought we knew about heart health.

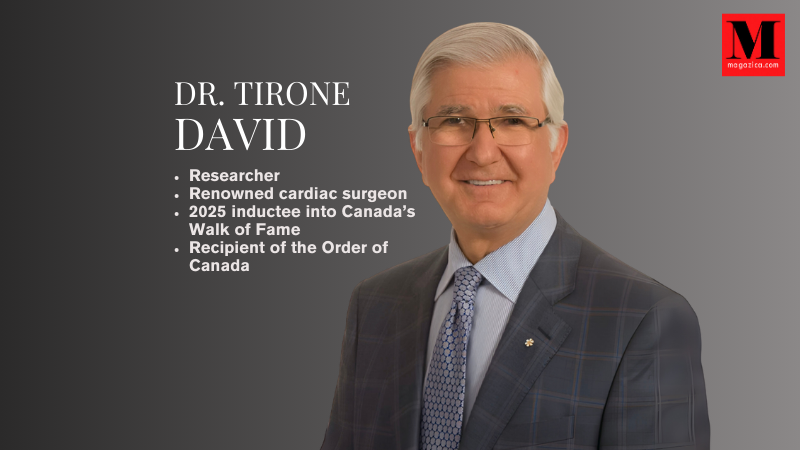

Magazica: Dear readers, it’s a privilege and an honor to welcome Dr. Tirone David to our conversation today. Dr. David is an internationally celebrated cardiac surgeon, a pioneer in cardiovascular procedures, and a dedicated innovator in healthcare. With a career spanning over four decades, he has performed more than 15,000 open-heart surgeries, contributed to 16 groundbreaking surgical techniques, and authored over 450 scientific papers. His passion for advancing medicine remains undiminished as he continues to operate twice weekly at University Health Network’s Peter Munk Cardiac Centre in Toronto.

He is a 2025 inductee into Canada’s Walk of Fame and a recipient of the Order of Canada, embodying excellence and humility. Dr. David’s story is one of lifelong learning, mentorship, and an unyielding curiosity that has pushed the boundaries of medicine. Let’s dive into the story of a legend who continues to inspire countless lives.

Dr. David, welcome to Magazica.

Dr. Tirone David: Thank you. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Magazica: First of all, congratulations on being a 2025 inductee into Canada’s Walk of Fame.

Dr. Tirone David: Thank you. It’s a wonderful honor.

Magazica: Your career spans decades and is marked by numerous groundbreaking achievements. What was the moment or experience that first inspired your passion and dedication for cardiac surgery?

Dr. Tirone David: Well, my father told me to become a doctor, but I wasn’t very keen on the idea at first. Growing up in Brazil, before my teenage years, one of my uncles was a pharmacist. Back in the forties and fifties, pharmacists were very different from today. They were what we called “compound doctors,” mixing different substances to create medicines that treated pneumonia, diarrhea, and other ailments.

I was fascinated by the chemical reactions involved. My uncle taught me how to weigh milligrams using ultra-sensitive scales. The idea that you could divide a gram into a thousand parts and measure a single milligram fascinated me. I thought chemistry was my future.

But my father had different plans for me. He said, “No chemistry. We already have a chemist in the family—you’re going to be a doctor.” In Brazil, you start medical school at 17 or 18, and at that age, you don’t know much. In the first two years, you don’t see patients—you study basic sciences like anatomy, physiology, and pathology. You dissect cadavers, but you don’t practice medicine yet.

At 17, I wasn’t entirely convinced about chemistry anymore, so I started medical school—and it was magical. I discovered a part of myself I didn’t know existed. I was fascinated by the human body, its physiology, and its structure. Why are our hands shaped the way they are? I learned that the body evolves in an optimized form to fulfill its function—a necessity for survival.

As I progressed, I met my first mentor, Dr.Giocondo Artigas. He was an extraordinary surgeon, a technician unlike any other. I worked at a Catholic hospital, moonlighting to earn extra money. As I observed surgeries, I noticed that while most surgeons required pints of blood for transfusions, Dr. Artigas could perform complex abdominal operations with minimal blood loss.

I asked him how he did it, and he said, “Because I know anatomy. I know where to cut and where to sew. If you don’t cut blood vessels, they don’t bleed.” It was a revelation. Not all human beings are the same, and I gravitated toward his kind of excellence.

For the next 4 years, I worked with him, and he kept telling me, “If you want to learn beyond what I’ve taught you, you need to move away from Brazil. You have to go to the source where all these operations originated.”

My father admired Americans, and he encouraged me to come to the United States. I arrived as a surgical intern in New York, and during my internship, I realized that I wanted to focus on blood vessels, the heart, and arteries.

After completing my internship, I began searching for a training program that specialized in both vascular surgery—surgery of the arteries and veins—and heart surgery. I found the right program, and here I am. I never left Toronto. My journey took me from New York to Cleveland, then from Cleveland to Toronto, where I have remained ever since.

Throughout my career—from medical school to now—I have learned that mentorship is incredibly important. People who guide you in life shape your journey. First, you must respect them. You find someone you admire, someone you respect, and if there is a reciprocal mentor-mentee relationship, they will help direct you toward what you should pursue in life.

Magazica: Yes. We are very thankful to your mentor for guiding you and shaping your career, your growth, and your contributions here in Toronto. As Torontonians, we are grateful to you.

Dr. Tirone David: Mentorship even helps you redefine what you do in life. It’s easy to go to work, do your job, return home, and forget about work. But my mentors taught me to think critically. They taught me to ask, “Why?” If something doesn’t work well, seek a better answer—but before finding a better answer, you must first have a complete understanding of everything that currently exists in the field. Knowledge is the most important foundation for developing new concepts.

Magazica: Definitely.

Dr. Tirone David: Medicine follows the same principle. The approach I like to use is stepwise: you learn something, master it, then recognize its imperfections. Your goal should be to refine it without causing harm. This requires a delicate balance—being overly aggressive or overly inventive without responsibility can harm the patient. And that’s the key—every decision impacts a human being.

I have learned many things through experience—by analyzing what I’ve done and observing its effects on patients. If the outcome isn’t perfect, I try to understand why and modify what needs improvement.

Magazica: So first, you mastered all the available information, then you worked on refining and perfecting the process.

Dr. Tirone David: Yes, that’s a great way to put it. You must first understand an object completely—gain as much knowledge as possible—before attempting to modify it.

Magazica: That aligns perfectly with our next question. You have performed over 15,000 open-heart surgeries, which is an incredible feat. Based on your approach of refining knowledge through practice and reflection, what drives your focus and preparation each time you enter the operating room?

Dr. Tirone David: First and foremost, surgery requires an intense level of attention and focus. I believe in details—no aspect of patient care is unimportant. From preoperative assessments to diagnostic tests, every step matters. When you offer surgery as a treatment, you must recognize that it exists because there is no better alternative.

Surgery itself is archaic. We take a flawed part of the body, reshape it, remove it, or replace it. But why does that part become abnormal in the first place? The future of medicine lies in understanding these abnormalities and reversing them chemically and structurally—restoring the body’s natural state.

That is where medicine should be heading—not where I am today. But in the meantime, we must continue to keep people alive, functioning, and thriving.

What we do today in surgery might seem completely outdated centuries from now. If someone listens to this conversation a thousand years from now, they might call me an archaic dinosaur, wondering why we resorted to cutting a human body to fix a malfunctioning part. The very idea of creating harm through surgical incisions in order to repair an issue might seem primitive.

Nevertheless, I’m realistic enough to recognize that in 2025, surgery remains the state of the art for treating many conditions. I don’t know whether it will take 1,000 years or just 50, but eventually, surgery as we know it will become obsolete.

That said, surgery is, at its core, a type of therapy—it exists because there is no better alternative for addressing a malfunction in the body.

To truly innovate, one must first understand everything that preceded one’s work. Only by knowing the full scope of prior knowledge can a surgeon execute a procedure that modifies or improves a malfunctioning part of the body—in my case, the heart.

Throughout my 45-year career, every surgical innovation I’ve contributed has aimed to enhance function beyond its prior state—whether by cutting, stitching, modifying, or adding tissue to correct abnormalities.

I am highly critical—of myself, my colleagues, and my field. It’s part of my personality. But I’m also deeply analytical and open-minded enough to recognize that perfection is unattainable. What I do might be excellent, but it will never be perfect.

Magazica: Imperfection may be unavoidable.

Dr. Tirone David: Perhaps. But if I don’t strive for perfection, how can I improve? The only way to make something better is to aim for an unattainable ideal.

That relentless pursuit of perfection is what drives innovation.

My very first innovation happened when I was still a student. A new material, polypropylene, had just been introduced, but surgeons found it too bulky for closing abdominal incisions. In slender patients, the knots protruded through the skin.

I decided to bury the knots deeper within the tissue to prevent them from being felt post-surgery. That small technique became the subject of my first published paper—something simple, yet profoundly impactful for patient comfort.

Even small technical improvements can make a major difference. Why not pursue them?

Magazica: That’s fascinating. Two qualities really stand out—your analytical mindset and your critical approach. They seem to drive your meticulous, detail-oriented decision-making.

I also had a shift in perspective today. Surgery is not just about fixing something—it’s about healing and enhancing functionality beyond the patient’s preoperative state.

Dr. Tirone David: Absolutely. That’s exactly the essence of it.

Magazica: Fantastic. Your approach—being critical of your own methods to enhance outcomes—is universally applicable. Anyone can adopt that principle in their own field.

You’re still actively operating and innovating. How do you maintain your focus and energy?

Dr. Tirone David: Twice a week is my official schedule—but there’s no such thing as part-time heart surgery.

Years ago, I thought two days a week would suffice. I had gained proficiency; I didn’t need to learn new surgical techniques anymore—I just needed to perform them.

But last week, for example, I ended up operating five days in a row. On Friday, I started at 9 AM and didn’t leave the operating room until 2 AM. There was an emergency—a patient with multiple previous heart surgeries whose condition was deteriorating. Every part of their heart required reconstruction or re-reconstruction. It was complex.

So those two days often become three, four, or five.

Magazica: That’s incredible. It makes my question even more relevant—how do you sustain your energy and focus, especially considering how demanding cardiac surgery is?

Dr. Tirone David: To be honest, it’s largely mental. Let me give an example. I told my doctor that I was getting up two or three times a night to use the bathroom. When that happens, you go to bed at midnight, wake up at 3 AM, fall asleep again, and then wake up at 5 AM—your night is essentially over, and you’re exhausted the next day.

She told me, “It has nothing to do with your prostate. Forget about your prostate—it’s in your brain.” I asked, “What do you mean, my brain?”

She explained, “I’ve watched you in the operating room. You perform 12-hour surgeries without ever leaving to go to the bathroom. Why is that?”

Magazica: That’s fascinating.

Dr. Tirone David: The brain produces a hormone called the antidiuretic hormone. For instance, last Friday, I started surgery at 4 PM and finished at 2 AM—10 hours straight. Yet, during that entire time, I didn’t need to empty my bladder, because it wasn’t filling up.

My brain produced the antidiuretic hormone, which prevents urine production. This is scientifically sound—it’s a natural response. When you’re fully engaged in solving a complex problem, your body prioritizes the task at hand, shutting down non-essential functions. That’s why I said it is largely mental.

Magazica: That’s laser-like focus.

Dr. Tirone David: Exactly. My body, my hormones, everything works in synchrony to execute the job. Of course, the moment I finish the surgery, I immediately have to use the restroom, because now I’ve relaxed—the patient is stable, the operation is done, and my bladder tells me, “Now is the time.”

That’s just one example. The brain produces far more than just antidiuretic hormones. It also releases endorphins—natural painkillers. If I have a sore knee or back, I won’t feel it in the operating room, because my brain is blocking out everything except the task at hand.

Magazica: Endorphins—sometimes referred to as the body’s natural morphine.

Dr. Tirone David: Precisely.

When I step into the operating room, I am transformed. My focus narrows to one thing—the patient and the operation. It’s often said in medicine that doctors should not treat close friends or family members, but I have operated on several friends.

Magazica: Really?

Dr. Tirone David: Yes, and they understand how I approach surgery. The moment they are draped for the procedure, they are no longer my friends—they are patients with medical challenges that I must solve. It doesn’t matter who is behind the surgical drapes—they could be my wife, my neighbor, or a stranger. I treat them all the same, because my duty is to solve their health problems. They have entrusted me with their care, and I am committed to doing my job.

Magazica: A professor of mine once said, “You must remove emotion from decision-making to achieve excellence.”

Dr. Tirone David: That’s true, but easier said than done, especially when dealing with life-or-death situations. For instance, sometimes I see a very sick patient and instinctively know—based on my experience—that surgery would be too risky. But the intense desire to help a suffering individual can sometimes override reason.

I must admit, I have made that mistake before. A patient I had first operated on when she was 18 came back to me decades later. She had wanted children, so I initially avoided a more invasive procedure for her. Then, at 45, she returned—her condition had worsened, and other doctors advised me not to operate because she wouldn’t survive.

But she was miserable—her quality of life was deteriorating. I chose to operate. She didn’t die, but a month later, she wasn’t any better than before. The procedure ended up being futile.

Magazica: The desire to help a suffering soul can be powerful.

Dr. Tirone David: Yes, but sometimes it can lead to emotionally driven decisions. One of the most profound hospital mottos I’ve ever seen was at Padre Pio Hospital in Puglia, Italy. Above the entrance, there was an inscription that translated to, “A house to alleviate human suffering”

That is the essence of medicine. Doctors and hospitals exist to alleviate suffering.

Magazica: And you’ve done that in remarkable ways over your 45-year career—pioneering 16 surgical procedures.

Dr. Tirone David: Out of the 16 procedures I developed, perhaps nine or ten were truly original—ideas that had never been conceived before. The rest were modifications of existing techniques aimed at improving them, pushing them closer to perfection.

Magazica: For those nine or ten groundbreaking discoveries, can you share the story behind one? What motivated you, and what was the thought process behind it?

Dr. Tirone David: One of the simplest but most impactful discoveries happened in 1985.

By that time, it was widely understood that if a heart valve was malfunctioning, the standard treatment was replacement. However, valve replacements were far from perfect—they improved a patient’s condition but had several long-term complications. We realized that, whenever possible, repairing a patient’s own valve yielded far better outcomes. However, a poor repair was worse than a replacement.

This created a complex, gray area—choosing between repair and replacement wasn’t always clear-cut. As surgeons, it became our responsibility to refine our judgment, moving closer to definitive solutions.

Back in 1985, most surgeons specializing in mitral valve disease could only repair about half of the affected valves. The available techniques were limited.

While traveling, I visited a professor in New York City experimenting with Gore-Tex in a laboratory. He was testing its use for replacing tendons and other fibrous cords in the body. I observed his work and asked if he minded if I attempted to use the material in human heart surgery. He encouraged me to try.

I returned to Toronto and began experimenting, first using Gore-Tex in animal models—six pigs—to understand its effects. Once I was satisfied with the approach, I applied the technique in human surgery, replacing the affected valve structures instead of replacing the entire valve.

I performed the surgery, then waited cautiously. After two to three months, I performed an echocardiogram on the patient—it was perfect. I waited another three months—still perfect.

That gave me the confidence to proceed with another case, and another. Within five years, by 1990, I had performed the procedure on over a hundred patients, with none experiencing failure.

At that point, it was clear—I had stumbled upon something transformative. We published the results and shared them with the international medical community. The technique soon became widely adopted.

The concept itself was simple: replacing a fibrous cord that supports the heart valve rather than replacing the entire valve. Yet it had a profound impact—it saved at least half of the patients who would otherwise require full valve replacement.

Alternative repair methods existed, but none were as durable. Many failed after a few years, while my technique remained effective—as long as it was performed correctly.

This seemingly small modification completely changed patient outcomes for mitral valve repair and eventually proved useful for all four heart valves.

Another significant breakthrough involved the aortic valve. Before 1985, if a young patient—often teenagers or adults in their 20s and 30s—came in with an aneurysm in the ascending aorta, the standard operation was the Bentall procedure. Developed by Hugh Bentall, it involved replacing the entire aorta with a synthetic Dacron conduit and placing a mechanical valve inside it. While effective, it forced young patients to rely on artificial valves for life.

I learned the Bentall procedure and performed it frequently. But one day, I saw something remarkable—a 16-year-old patient’s aortic valve was pristine, completely normal. The supporting tissue was failing, but the valve itself was perfect.

It struck me—why was I replacing the entire system when only the surrounding tissues were defective?

Instead of following the standard protocol, I decided to replace the supporting structures while leaving the natural valve intact. I didn’t tell anyone about the deviation at first—just the parents, who were eager for a solution that would avoid an artificial valve.

Years later, this approach became a recognized surgical technique, preventing thousands of young patients from unnecessary valve replacement.

I monitored the first patient closely for a month, then two, then three. She remained in perfect health.

Magazica: Fantastic.

Dr. Tirone David: Encouraged by the success, I offered the procedure to a second child, then a third. From 1985 to 1992, I performed this new operation multiple times.

This technique was entirely revolutionary, unlike anything that had been done before. Eventually, the procedure was named after me—it became known as the “David Procedure.” Though there have been variations over time, the core principle remains: preserving the patient’s natural valve when the surrounding tissue is failing.

Magazica: That’s incredible.

Dr. Tirone David: This innovation has had a major impact on life expectancy and quality of life for patients. By preserving their natural valve, they avoid complications associated with artificial replacements, leading to better long-term outcomes.

Magazica: Hearing these stories—the way they unfolded, the positive impact on human lives—it’s truly inspiring.

Many of our readers seek inspiration in making healthier lifestyle choices. From your vast experience, what are the key actions individuals can take to protect their heart health?

Dr. Tirone David: I wish I had a definitive answer. Most advice on heart health consists of well-known principles: don’t smoke, stay physically active, eat well, and avoid unhealthy foods.

Unfortunately, even if someone follows all these guidelines, one major component of heart disease is not easily modifiable—genetics. Our hereditary makeup plays a significant role.

Magazica: That’s true.

Dr. Tirone David: However, even genetics can now be modified, at least to some extent.

Let me share a personal story—I have a family history of high cholesterol. My mother had it, and two or three of her children, including me, inherited it. By age 32, I was already a fully trained heart surgeon, yet I knew I had high cholesterol.

I met a Hungarian cardiologist, a brilliant woman who guided me early in my career. She frequently traveled to Europe and had extensive knowledge of European medicine. She told me about a medication being used in England and other parts of Europe to lower cholesterol by blocking its production in the liver.

She suggested that I start taking it. At first, I was resistant—I never liked medication. But she insisted, saying, “It might make a difference in your life.”

Eventually, I began taking statins, which prevent cholesterol buildup. That decision was a turning point—statins significantly reduce the risk of heart disease and heart attacks. They also have pleiotropic effects—unexpected but beneficial additional properties.

I never worried much about my heart health until I turned 70. That’s when I decided to undergo my first cardiac test.

The technician reviewing my results called me and said, “There’s something wrong with your chart. It says you’re 70 years old.” I replied, “I am 70.”

He said, “No, you’re not—not based on your test results. Your arteries look like those of a 35-year-old.”

Magazica: That’s incredible.

Dr. Tirone David: I attribute that solely to my proactive decision to modify my genetic cholesterol profile. There are now many other discoveries emerging in this field, showing that genetics can be influenced.

Magazica: So, in summary, what key health actions would you recommend?

Dr. Tirone David: The well-known risk factors still apply:

Magazica: We’re nearing the end of our conversation, but before we wrap up—throughout this discussion, your humility has been remarkable. It was even mentioned in your professional introduction. What role do humility and curiosity play in driving innovation in your field?

Dr. Tirone David: Scientific arrogance is one of the worst qualities an investigator can have. The moment a scientist believes he or she knows everything, he or she is bound to fail.

Magazica: That’s a powerful statement.

Dr. Tirone David: My humility comes from the knowledge that I don’t know everything.

I have shared stories from my career, but I am well aware that within the next decade or two, someone will likely dismiss my techniques as outdated. Science evolves, and what is cutting-edge today may be archaic tomorrow.

Understanding that is what keeps me humble.

I may be highly skilled right now, but my knowledge applies only to this era. That’s why curiosity is critical—it drives progress. The ability to keep asking questions leads to better solutions.

You must be inquisitive in whatever you do. It applies to all professions—whether you are a musician, an architect, a cleaner, or a garbage collector. If you keep thinking of ways to improve your craft, you will inevitably make things better.

Magazica: That’s a profound perspective. One last question—do you have any dreams you hope to fulfill in the near future? And what advice would you offer to young professionals, particularly aspiring cardiac surgeons and specialists?

Dr. Tirone David: I think it’s extremely important to love what you do.

If you wake up in the morning and feel like your work is a burden, thinking, Oh no, I don’t want to do this today, then maybe it’s time to find something else.

If nothing interests you, I won’t have much advice. But if you can seek out something that excites you—something that makes you feel alive and eager to keep going—that’s one of the secrets to happiness. When you’re passionate about your work, you naturally do it well.

Magazica: That’s an insightful perspective. And what about your dreams for the future—your mission or vision for cardiac health and treatment?

Dr. Tirone David: At my age, my primary focus is to stay physically and mentally well, so I can continue doing what I love.

That being said, I also recognize that life is finite. Eventually, I will have to step away and say, Well, that was my contribution—thank you. At that point, I’ll probably learn to play golf and go fishing.

But for now, I remain dedicated to my work.

Magazica: What an extraordinary career you’ve had! It’s remarkable, contributory, and even philanthropic. Whatever words I use, they still fall short in capturing the full scope of your impact.

Dr. David, thank you for sharing such valuable time with us, offering incredible insights for our readers and viewers. We truly appreciate it.

Dr. Tirone David: The pleasure was mine.

- Share

Dr. Tirone David

Dr. Tirone David is a world-renowned cardiac surgeon and a pioneer in cardiovascular procedures, credited with transforming heart surgery through innovation and precision. With a distinguished career spanning over four decades, he has performed more than 15,000 open-heart surgeries and introduced 16 groundbreaking techniques that have reshaped modern medicine. A prolific researcher with over 450 scientific publications, he continues to operate at University Health Network’s Peter Munk Cardiac Centre in Toronto. A 2025 inductee into Canada’s Walk of Fame and a recipient of the Order of Canada, Dr. David embodies excellence, mentorship, and an unyielding drive for medical advancement.